This is republished content originally hosted on the Mercatus’ Center former blog, Neighborhood Effects.

You’d think that eight years after the financial crisis, cities would have recovered. Instead, declining tax revenues following the economic downturn paired with growing liabilities have slowed recovery. Some cities exacerbated their situations with poor policy choices. Much could be learned by studying how city officials manage their finances in response to fiscal crises.

Detroit made history in 2013 when it became the largest city to declare bankruptcy after decades of financial struggle. Other cities like Stockton and San Bernardino in California had their own financial battles that also resulted in bankruptcy. Their policy decisions reflect the most extreme responses to fiscal crises.

You could probably count on both hands how many cities file for bankruptcy each year, but this is not an extremely telling statistic as cities often take many other steps to alleviate budget problems and view bankruptcy as a last resort. When times get tough, city officials often reduce payments into their pension systems, raise taxes – or when that doesn’t seem adequate – find themselves cutting services or laying off public workers.

It turns out that many municipalities weathered the 2008 recession without needing to take such extreme actions. Studying how these cities managed to recover more quickly than cities like Stockton provides interesting insight on what courses of action can help city officials better respond to fiscal distress.

A new Mercatus study examines the types of actions that public officials have taken under fiscal distress and then concludes with recommendations that could help future crises from occurring. Their empirical model finds that increased reserves, lower debt, and better tax structures all significantly improve a city’s fiscal health.

The authors, researchers Evgenia Gorina and Craig Maher, define fiscal distress as:

“the condition of local finances that does not permit the government to provide public services and meet its own operating needs to the extent to which these have been provided and met previously.”

In order to determine whether a city or county government is under fiscal distress, the authors study the actual actions taken by city officials between 2007 and 2012. Their approach is unique because it stands in contrast with previous literature that primarily looks to poorly performing financial indicators to measure fiscal distress. An example of such an indicator would be how much cash a government has on hand relative to its liabilities.

Although financial indicators can tell someone a lot about the fiscal condition of their locality, they are only a snapshot of financial resources on hand and don’t provide information on how previous policy choices got them to their current state. A robust analysis of a city’s financial health would require a deeper look. Looking at policy decisions as well as financial indicators can paint a more complete picture of just how financial resources are being managed.

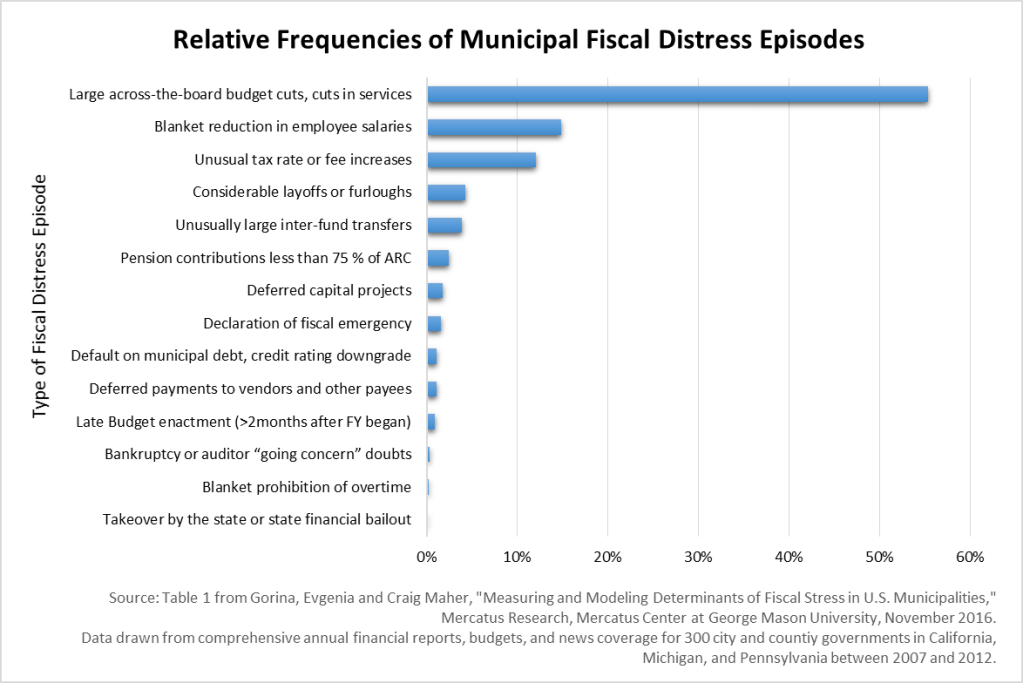

The figure here displays the types of actions, or “fiscal distress episodes”, that the authors of the study found were the most common among cities in California, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. As expected, you’ll see that bankruptcy occurs much less frequently than other courses of action. The top three most common attempts to meet fundamental operating needs and service requirements during times of fiscal distress include (1) large across-the-board budget cuts or cuts in services, (2) blanket reduction in employee salaries, and (3) unusual tax rate or fee increases.

Another thing that becomes clear from this figure is that public workers and taxpayers appear to be adversely affected by the most common fiscal episodes. Cuts in services, reductions in employee salaries, large tax increases, and layoffs all place much of the distress on these groups. By contrast, actions like fund transfers, deferring capital projects, or late budget enactment don’t directly affect public workers or taxpayers (at least in the short term).

I decided to break down how episodes affected public workers and taxpayers for each state examined in the sample. 91% of California’s municipal fiscal distress episodes directly affected public employees or the provision of public services, while the remaining 9% indirectly affected them. Michigan and Pennsylvania followed with 85% and 66% of episodes, respectively, directly affecting public workers or taxpayers through cuts in services, tax increases, or layoffs.

Many of these actions surely happen in tandem with each other in more distressed cities, but it seems that more often than not, the burden falls heavily on public workers and taxpayers.

The city officials who had to make these hard decisions obviously did so under financially and politically intense circumstances; what many, including researchers like Gorina and Maher, consider to be a fiscal crisis. In fact, 32 percent of the communities across the three states in their sample experienced fiscal distress which, on its own, sheds light on the magnitude of the 2007-2009 recession. A large motivator of Gorina and Maher’s research is to understand what characteristics of the cities who more quickly rebounded from the Great Recession allowed them to prevent hitting fiscal crisis stage in the first place.

They do so by testing the effect of a city’s pre-existing fiscal condition on their likelihood to undergo fiscal distress. After controlling for things like government type, size, and local economic factors, they found that cities that had larger reserves and lower debt tended to weather the recession better relative to other cities. More specifically, declining general revenue balance as a percent of general expenditures and increases in debt as a share of total revenue both increase the odds of fiscal distress for a city.

Additionally, the authors found that cities with a greater reliance on property taxes managed to weather the recession better than governments reliant on other revenue sources. This suggests that revenue structure, not just the amount of revenue raised, is an important determinant of fiscal health.

No city wants to end up like Detroit or Scranton. Policymakers in these cities were forced to make hard choices that were politically unpopular; often harming public employees and taxpayers. Officials can look to Gorina and Maher’s research to understand how they can prevent ending up in such dire situations.

When approaching municipal finances, each city’s unique situation should of course be taken into consideration. This requires looking at each city’s economic history and financial practices, similar to what my colleagues have done for Scranton. Combining each city’s financial context with principles of sound financial management can surely help more cities find and maintain a healthy fiscal path.